Miguel A. Escotet: «Today there is a need to educate for uncertainty»

An Interview with Gena Borrajo, Eduga Journal, Spain.

Presently, he is the president of Afundación and IESIDE in Spain. Also, he is an emeritus professor and former Dean of the UTRGV College of Education at the University of Texas. Miguel Angel Escotet has conducted in-depth studies about American (North and South) and European university reforms, thus becoming a well-known expert on the subject. In this interview, he reveals the key factors for achieving an education adapted to modern times. To his mind, it is crucial to allow students take a more active role in their own education, to strive for a balance between the cognitive and affective domains and educate for an increasingly uncertain world.

Educating for uncertainty. Sounds difficult…

It is indeed difficult, but absolutely necessary. And it is a complex issue because we have created a world in which there is a great deal of fiction. We think that everything has already been done. There is too much talk about strategic planning, about designing programs for students who are just beginning their lives and who will remain in the formal education system during sixteen years, but it is almost impossible to know what will happen by the time they will join the job market. The fact is that we lead them to believe that with what they are learning their future will be solved, when it would be more reasonable to help them build that future.

What are the pillars that provide support for this theory?

The basic foundation in educating for uncertainty is to teach students to think, to dissent, to tolerate and respect other people. And these are affective, not cognitive dimensions. Spanish education is highly cognitive, which is all well and good, as long as it is not at the expense of the affective aspects, since the human being must learn to live within society. What this school of thought proposes is figuring out how to help students solve their problems by providing them with tools and, of course, know-how. And this isn’t something that can be achieved with rigid programs.

Apart from your engineering studies, you’re also a psychologist. Is it psychology that has determined your way of focusing on education?

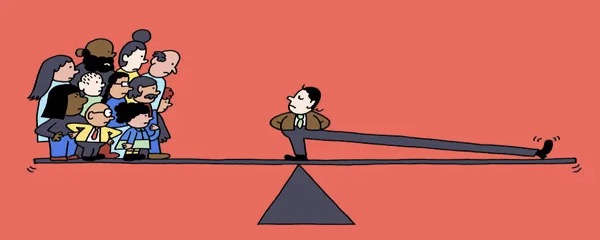

It has helped me to center my attention on the student. In the university, we have a tendency to develop a curriculum for each course created in the image of what the professor knows, which prompts a crisis, since what the student ought to acquire is the knowledge that the world demands from him or her. Within the framework of this viewpoint, the knowledge that is really important often arrives too late. That is to say, we are behind the times. It is as if we were repeating history instead of making it. What I mean by this is that the European university – and perhaps the American university too, I’m not saying this isn’t the case – thinks a lot more about the teacher than about the person being taught.

Is this new way of teaching a question of concept or of resources?

Both. On the one hand, it involves a concept of university education. In the curriculum there must be core contents that everyone needs, but you also have to leave spaces to be shared, in which the student can hold opposing views . This way of teaching is more expensive because it requires more professors, the diversification of contents and less crowded classrooms.

With regard to group size, should it be related to the type of subject taught?

It can, but on this point we find a widespread error: We’ve often thought that the exact sciences (mathematics, for example), should be taught in small groups and that philosophy can be given in large classes, when actually just the opposite is true. Students can follow the process of an equation on a screen, what it derives into, how it is reconstructed, how it is defined and how it is solved. However, under these conditions, it is very difficult to explain a theory by Aristotle and hope that everyone will reach the same deduction, because in that case, reconstructive thinking is necessary, and this requires analysis and discussion. When this is left out of the mix, it is easy to fall into simple rote learning.

Well, now, you’re dismantling the old myth about sciences and humanities.

There is a concept asserting that theoretical subjects are easier to teach than those of a more practical nature, and that’s not true. Moreover, a dichotomy has been created between the humanities and science. Two languages have emerged that are at odds with one another, and there is certain contempt of one for the other, even within the scientific field. That’s a problem. I have studied engineering, clinical psychology, philosophy and education, and I can state that mathematics is the most uncomplicated thing to learn, because it has to do with an easily grasped system of symbols. The thing is, when we impart disciplines that are considered theoretical, we fail to teach people to think, because we believe that the teaching of reasoning skills is associated only with science.

You are very familiar with the European and American university systems. What is your view of EHEA (European Higher Education Area)?

Convergence is a way of harmonizing the higher education system as a whole in the European Community. This, as stated, seems good to me. But you can’t really say that this is a perfect reform, since it has copied part of the Anglo-Saxon model, which, in my opinion, has certain weaknesses. They should have been more selective – that is to say, they should have taken the good parts into account and kept what functioned well in the already existing European system.

Which are those weakest points?

First of all, as I’ve already said, university education continues to be too oriented toward the faculty, the department, or even toward the administration, which I see as a serious drawback, since while it is true that a management system is essential, it should be borne in mind that it must always be at the service of the consumers – in this case, the students. One example is the very organization of the curriculum into credits, which is nothing more than an adaptation designed to satisfy the wishes of the professors and not the needs of the students.

What do you mean?

Well, that when it comes to establishing the duration of studies, the criteria can’t be one size fits all, because what one person can do in a shorter time, another person will require a longer time to do. In other words, the reduction that has been carried out translates as “studies on the run”, but the criterion to apply should be that studies should last as long as needed, determining the time on case-by-case basis. I insert university education into a life-long education project. Therefore, I insist, individual differences must be respected, and this is something that is not contemplated within the model that we’re referring to. In point of fact, the United States is learning toward the European concept of education, while here in Europe, we’ve been there and now are going back to the other end. No one is completely right.

Having reached this point, is there any possibility of solving that time shortage to which you refer?

We face a situation that poses the need to find a very good balance between generality and specialty. We cannot train a professional in the skills that pertain to his/her field of study at the cost of reducing general contents. This is what has happened with the Master’s degree which was conceived for those who already had a solid foundation, but now we have to give up that concept in order to cover a lot of ground in a short time.

Besides, theory and practice do not go hand in hand. Is it so hard to combine the two things?

The truth is that there are professionals who develop theoretical systems without testing them, when research should indeed have an empirical basis. Many times the origin of this is a sort of arrogance that keeps us from approaching the classrooms, because we believe that this is the job of the teachers in the earlier stages; this is an error. I don’t see why a professor at the university level can’t teach in primary or secondary schools in order to find out what’s going on there, before the students reach the university. We shouldn’t forget that the earliest learnings and teachings have an enormous influence on people. I’ve always held the opinion, for instance, that those who teach small children should be the best paid and the best educated, because it is at those ages that a foundation of vital importance is constructed: when language, feelings, are acquired…That is why I think that it is a good practice for those educating future teachers to spend some time in the school, because it’s impossible to conceive a professor for future teachers who doesn’t act like one of them, or who isn’t a model teacher him or herself.

So do you think, then, that education is too fragmented?

Yes I do. First of all, we segment it by level, and then we extend artificial bridges between one stage and another. In this way, it stops being a continuum. We need to create a model in which theory and practice go hand in hand and in which education is conceived as a lifelong process.

Did you work along these lines in your university?

As former university president and dean of education, I urged the professors to impart their disciplines within our experimental schools or the public schools. At present, we still don’t have it all figured out, but I am growing confident that this will become a reality in the near future. And that’s the idea, because I think that these are the proper venues for education, both at the undergraduate and graduate level. There, each professor who is just beginning his or her career is assigned a mentor – an experienced teacher who, for two or more years, helps the new faculty to develop his or her programs. This is the equivalent of what in Spain would be the catedrático (tenured professor), but in Spain the model is somewhat endogamous [“I support those who have worked with me”]. In the United States you can also experience this problem, but they have a system of rotation, which makes the process much more dynamic. They hire new faculty from a different university. In this way, the difference between experienced and inexperienced professors is considerably reduced.

Do you think that the adoption of a similar model would be difficult in Spain?

I would say that there are two issues that hinder a change in that direction: A system of oposiciones (civil service examinations) that has ended up as a protective shield, and retirement…

Retirement?

Yes. The retirement age should not be the same for all professions. A surgeon may not be capable of performing surgery past a certain age, but can indeed place his or her experience at the service of education. In Spain, we have created mythical numbers – 60, 65, 70… At those ages, a retiree quits placing his or her intellectual baggage at the service of the community, and by doing so, he takes away a cumulative experience of great value. In the end, the young professionals are the ones who suffer the consequences, since they end up taking refuge in an individualism that is detrimental to their own development, to the productivity of their work and to the economy as such.

And also to the retiree…

Naturally. Here there is a sick obsession with this issue and the discussion arising from it is more political and economic than professional. It is often argued that retirement makes way for the younger generations, which is not true either, since the European countries with the lowest unemployment rates are the ones that show the highest employment rate for young people, without having to cast aside the people with more experience. In the United States, people retire whenever they wish if there are in good health. As a matter of fact, you have great age diversity between presidents, deans, department chairs or faculty.

New technologies have come along and revolutionized society and even the family. Do you think that they have entered the education system with the same force?

Not at all. The equipment has come into play and the traditional blackboard has been replaced by a Power Point or a digital blackboard or tablet. But information and communications technologies, with everything that they imply, haven’t been introduced into teaching. This is just another chronicle in the history of education. It happened previously with radio, which was barely used as educational resource, despite the enormous potential of audio transmission for activating thought, because it demands reconstruction with the imagination. Television brought image and with it weaken the imagination. But today, when we go into the Internet, we are faced with not only sound and image, but also text. This makes youngsters think that the media give them great power, which is not true if they don’t know how to handle them.

As you say, computers have already entered the schools. Now what do we do?

Now is the time to create quality processes, in which technologies give rise to methodologies that mobilize teaching and learning. This implies a proficient faculty only in the handling but also in the application of those technologies. The fact is that youngsters usually have a greater dominion over these tools, but that doesn’t mean that the faculty can’t provide such tools with a critical use of them. For example, young people think that the information they obtain on the Internet is always real and true, when this isn’t the case. And that’s where they need the support of an expert to help them select and deal with this data.

Is the University faculty prepared to do this?

It’s proving very hard for the university to meet these challenges, fundamentally because a concept exists of a professor who teaches and students who learn. The scheme that teachers and students learn together doesn’t exist, not even in theory. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that technologies are utilized as a pretext, to put in “a few little things”. Another major problem is that the majority lack adequate pedagogical techniques, and this includes the pedagogues themselves. There is a great disregard for the principles of learning. We are much better trainers than educators, although this problem doesn’t affect all fields of study to the same degree.

Which ones come out on top?

In my experience as an evaluator, I have found a higher quality level among educators in engineering and medicine. And this is the case because in those disciplines theory and practice are closely associated. In medicine, for instance, there is an instrumental component, but also an affective one, since human life is involved. In education we haven’t incorporated that approach, because we think that learning badly is of no importance, when it is indeed of great importance. We must not forget that people’s mental health is involved. This is why it is so necessary to evaluate the teaching staff.

As they do in USA?

At some extent, yes. There, we have to demonstrate our competence every five or six years. As a tenured professor, you submit yourself to an evaluation by your students and colleagues and have to provide evidence that your contribution is beneficial to teaching, research and service if you want to continue your teaching career. And that’s the way it should be because chairing a department or program shouldn’t mean having carte blanche [to do what one pleases]. We have to be constantly up to date, not only in the field we teach, but also in technologies, in methodologies and so on. This is what’s demanded in order to keep a job, which, furthermore, contains a component of professional ethics: I can’t teach if I don’t know enough or don’t know how to do it.

Shouldn´t we start by giving a major leading role to the teaching within the university?

Yes. The research and teaching components must be in equilibrium. The two should go hand in hand, because teaching must be fed, in part, by the research of the professors themselves and by that of everyone else. But over and above that, the faculty should have a sense of social responsibility or, as I prefer to call it, a social commitment, because if they don’t assume this, it’s highly unlikely that they’ll be able to get their students to develop this feeling of community, which, furthermore, is one of their functions.

That demands dealing with students on one to one basis

That’s right. In the distribution of responsibilities, I would assign 50% of the time to teaching, 25% to research and the other 25% to social commitment. From there we could go into specific cases. Or in other words, in certain cases you would have to consider whether it might be advisable for a professional to be devoted exclusively to research because that’s the area where he or she really has a contribution to make. In point of fact, in the United States, there are three types of universities: research, mixed and teaching comprehensive institutions. I always recommend studying the first four years in an oriented teaching university, and afterwards, go during two, three or four years to a research university to get your graduate studies, specialitation or doctorate.

We´ve seen the problems of undergraduate education, but permanent education hasn’t provided the results expected either.

I believe that permanent education, professional development or lifelong learning requires a change of attitude and must be supplemented by incentives. We mustn’t forget that we have a powerful competitor – leisure with all its varied and attractive alternatives. The question is, how do we manage to get a community – that of Galicia, for instance – to instill into society the will to improve the qualification of its citizens? This is a question that must come prior, even, to the availability of a program of continuing education, and the incentives don’t necessarily have to be economic. The key is to create a need and this has a component that is more affective than cognitive. Sometimes we prepare interesting programs that are well organized and perfectly structured, but we fail to reach people’s heart and I think that this is where the big problem lies.

Today, the idea of mobility tends to be very much present when it comes to planning the curricula. In Spain we have a problem with languages.

Languages aren’t learned in a vacuum. They need spaces in which to practice them and live them. This is what is done in bilingual education. That doesn’t mean that the only road to take is living abroad. Evidently, spending some time in a place where the language we want lo learn is spoken help a lot, but no society can afford to send all of its citizens abroad. So you have to create environments within the country in which the students can speak [the language] and feel it, because learning languages has a great affective component to it. Things are changing, but until a very short time ago, English was taught by starting with grammar, so it should come as no surprise that we come in so low in all of these studies. Nor do I believe that language is the only thing that stands in our way when it comes to seeking a job abroad.

No?

We Spaniards are reluctant to move. When I was coming frequently to Spain, I have always found the same people in the same places, in the same job. Our aspirations center on having a lifetime job. We’re afraid to take risks. We look primarily for job security, not for self-realization. It forms part of our present culture and our way of being. It needs to be change.

In these times of grave crises, do you have any advice to give as the representative and guiding light for your institution?

We should take advantage of this troubled time in order to educate ourselves more and better, to administrate scarcity with criteria based on scarcity and to promote solidarity with people. But we also have to prepare ourselves for when the recovery comes. We have to stop such exaggerated consumption. And here, I return to the uncertainty theory: It is necessary to learn from experience, to realize that nothing is certain, and faced with such grave problems we need ingenious solutions, which you can’t achieve with a rigid education as we have.

A University Professor with the soul of a teacher

To get acquainted with Miguel Ángel Escotet is to follow a path throughout the length and breath of the world. We took advantage of his trip to Oviedo, where he agreed to give us this interview, a kind gesture if we consider that it forced him to move away from his busy schedule. The conversation was delightful: plenty of wisdom and cordial disposition. In a very pleasant chat, he was answering the questions and his words, far from finishing up an issue, gave cause for more and more questions. We realized very early in the interview that we were facing a university professor with the soul of a teacher.

His professional path is based on his multidisciplinary education. He studied Engineering, Philosophy and Clinical Psychology but education has been always the center of his interest. Clear proofs of it are the several positions he has held in U.S. besides Texas: full professor at Florida International University; Director of the International Institute of Educational Development and its programs of graduate studies; Director of Research and Evaluation of SABES, a Federal Center from Florida University System; Psychology professor at Fort Lewis College in Colorado, assistant professor in the University of Nebraska and visiting professor in all five continents.

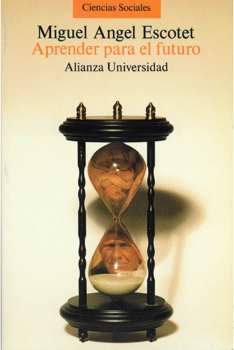

Education is also at the center of the research activities of this illustrious Spaniard: He has published fifty-two scholarly books and his major research in reform and innovation in higher education on Latin America, US and Europe as well as development of research methodology in cross-cultural psychology and transnational studies have taken up a good deal of his time. He is now back in Spain dedicating all of his time to direct one of the major foundations of the country sponsored by ABANCA, Afundación and its Institute of Higher Education, IESIDE.

Some of his books

- Estadística Psicoeducativa [Statistics for Psychology and Education] (1973) (10th Edition, 2013). Mexico, Editorial Trillas.

- Técnicas de evaluación institucional en la educación superior [Institutional Assessment Techniques for Higher Education] (1984). Madrid, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

- Aprender para el futuro [Learning for the Future] (1992) Madrid, Alianza Editorial.

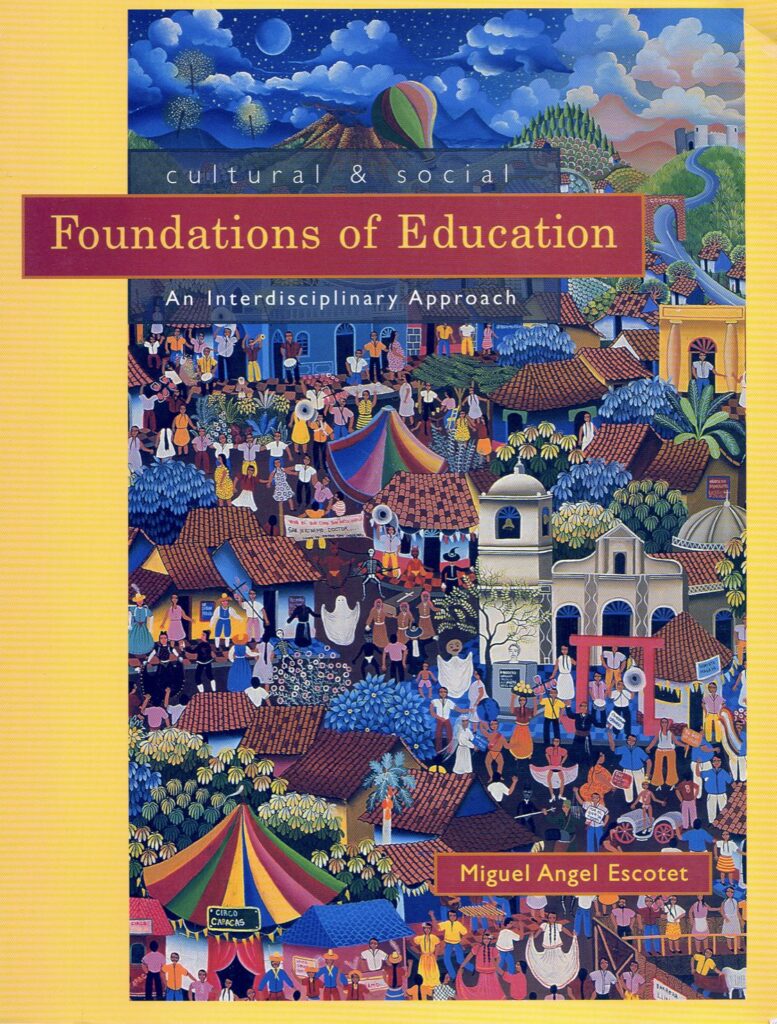

- Cultural and Social Foundations of Education: An Interdisciplinary Approach (1997). Boston, Simon & Schuster.

- Universidad y devenir: entre la certeza y la incertidumbre [University and Becoming: Between Certitude and Uncertainty] (2000). Buenos Aires, Lugar Editorial.

- The Psychosocial and Cultural Nature of Education with C.A. Alvarez (2004). Boston, M.A., Pearson Publishing.

- Modelo de innovación en la educación superior [A Model of Innovation for Higher Education] with A. Villa and J. Goñi (2008). Bilbao, Mensajero y Universidade de Deusto.

- La Actividad Científica en la Universidad [The Scientific Activity in the University] with M. Aiello & V. Sheepshanks (2010). Buenos Aires, U. Palermo, UNESCO and United Nations University.

- Análisis multivariado en ciencias humanas [Multivariate Analysis in Human Sciences] (2017). Miami, Transcampus,Inc.

Credits

This condensed interview was originally published by EDUGA Journal, #57, Spain. It is reproduced in English.

@2021 EDUGA & Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.

y más especializados. Pero el conocimiento más profundo de la materia y sus características nos lleva a una visión ínter y transdisciplinar y a una concepción unificadora del mundo, tanto en el dominio de las ciencias como en el de las humanidades. Las nuevas tendencias han vuelto a romper las fronteras artificiales que se habían establecido entre las diversas ciencias particulares. La aplicación del método científico en su más amplia acepción, identifica las ciencias con las humanidades, acercándonos a un humanismo científico-técnico, en donde la razón pura tiene que estar en equilibrio con el sentido de la estética, la ética y trascendencia del ser humano.

y más especializados. Pero el conocimiento más profundo de la materia y sus características nos lleva a una visión ínter y transdisciplinar y a una concepción unificadora del mundo, tanto en el dominio de las ciencias como en el de las humanidades. Las nuevas tendencias han vuelto a romper las fronteras artificiales que se habían establecido entre las diversas ciencias particulares. La aplicación del método científico en su más amplia acepción, identifica las ciencias con las humanidades, acercándonos a un humanismo científico-técnico, en donde la razón pura tiene que estar en equilibrio con el sentido de la estética, la ética y trascendencia del ser humano. and Click o modelo online o en línea. Es decir, el futuro de la educación, y muy en particular de la universidad, llevará a dos modelos genéricos: el de élite, que combinará educación presencial y a distancia como integración de la socialización académica y el conocimiento; y el modelo de masas como instrucción online o no presencial. Este segundo modelo será de gran utilidad para el inevitable y necesario reciclaje y actualización profesional que estará inserto de por vida en todas las profesiones y actividades laborales. Por supuesto, existirán modelos mixtos que integrarán partes de esas dos vertientes genéricas.

and Click o modelo online o en línea. Es decir, el futuro de la educación, y muy en particular de la universidad, llevará a dos modelos genéricos: el de élite, que combinará educación presencial y a distancia como integración de la socialización académica y el conocimiento; y el modelo de masas como instrucción online o no presencial. Este segundo modelo será de gran utilidad para el inevitable y necesario reciclaje y actualización profesional que estará inserto de por vida en todas las profesiones y actividades laborales. Por supuesto, existirán modelos mixtos que integrarán partes de esas dos vertientes genéricas.