Kristin Rosekrans

Harvard University

In this article, the author, who lives and works in El Salvador, analyzes the different levels of educational opportunity attained in this country, barriers to improving equity, and the potential effects on equity of current policies and programs. She offers a framework for analyzing educational opportunity as well as a model for improving equity through compensatory strategies to enhance educational quality for the poorest sectors.

Overview

In the past few decades, Latin American countries have undergone major transformations politically, economically, and socially – changes that, logically, are reflected in their education systems. Although there is a wide disparity of differences in the countries, some tendencies are reflected throughout the region, such as political systems moving from dictatorships towards more democratic systems, education reforms implemented shortly after this shift intending to strengthen democracy, and an emphasis on expanding access to basic education. Many of these efforts have been influenced by international organizations such as the World Bank and UNESCO, and developed under the frameworks for action laid out in international summits such as the World Declaration on Education for All in Jomtien, Thailand and its ten-year follow up in Dakar, Senegal.

The declaration puts emphasis on the need to guarantee access to a quality education for all children. It states that “basic learning needs…comprise both essential tools… and the basic learning content…required by human beings to be able to survive, to develop their full capacities, to live and work in dignity, to participate fully in development, to improve the quality of their lives, to make informed decisions, and to continue learning” (UNESCO, 2000, p. 15). In this declaration and Dakar’s action plan, there is a clear call for education policy aimed at improving access and quality for the whole population, and with special attention for the marginalized sectors and “children in difficult circumstances” (UNESCO, 2000, p. 15). In line with these guidelines, Latin American countries throughout the last decade have used strategies that appear to be aimed at improving access and quality for these sectors. Although the reforms have taken a different shape in each context, some of their common threads have been: (a) decentralization, (b) increasing community participation and school autonomy, (c) improving access and, (d) various initiatives to improve quality such as curricular reform and training and incentives for teachers.

However, while there seems to be clear evidence that access has improved in the majority of Latin American countries, it is much less clear that quality has improved. Providing schools, desks, materials, and teachers for populations who had been deprived of these basic inputs, is certainly one step closer to achieving basic learning needs. Passing management to a local level, to communities who previously had no say in any educational decisions, may be one step closer creating a democratic system and increasing parental involvement. Reforming the curriculum to a more constructivist approach and training teachers to employ this curriculum may improve the practice of some teachers – especially those with enough basic knowledge and pedagogical skills to add this to their repertoire of teaching practices. For the least competent teachers, who tend to serve the most marginalized children, it may not do much towards helping these children to develop their full capacities and to improve the quality of their lives. In order to have impact at this level, for this population, policies and programs may have to take on a new form.

In the context of Latin America, as in the case in many regions of the world, it is important to not overlook issues of equity. High levels of inequality, often characterized by a small portion of the population controlling the majority of the resources, often leads to a lack of political stability and stunted overall social development. It was the high level of inequality that lead up to El Salvador’s civil war, as also occurred in many other Latin American countries throughout the past few decades. As argued in this paper, access to educational opportunity is very important in order to create a more equitable society. It is not, however, the only essential factor: A move towards a more equitable society entails policy changes in the economic, political, and other social sector dimensions. Yet, moving towards more equality of educational opportunity is a step towards a more equitable society, hence a higher overall level of social development and more political stability.

While assessing whether or not educational opportunity has improved in a particular country or region, it is important to be clear both about the criteria for what constitutes equality of educational opportunity and about the criteria for assessing the best way to achieve equality. In this paper, I attempt to do this by analyzing the barriers to educational equality of one particular Latin American country, El Salvador, through a framework of educational opportunity that is multi-layered and on a continuum. Furthermore, I propose a model for the necessary conditions for providing equality of opportunity and criteria for assessing and working towards this model.

The hypothesis of this paper is that that to improve educational opportunity, the most marginalized sectors of society must have the possibility to change their life circumstances, and that this is not possible without policies based on a more complex model of equality of educational opportunity that goes beyond mere access to formal schooling. This does not rest on the assumption that access is not important; rather that education should offer the possibility for individuals to transform their lives. This is not the case, however, for the many children repeating grades, dropping out of school in the early grades, and never completing secondary education. What makes a difference for these children may not be attending school, but the type of school they attend.

The first part of the paper lays out the framework for analyzing educational opportunity. The second part is a discussion of the degree to which educational opportunity has been achieved at each level in El Salvador and an identification of the possible causes and barriers to achieving equality of educational opportunity. This is followed by an analysis of the policy responses to this inequality and a discussion of other policy options. The last section draws from research-based literature of school improvement and school effectiveness to offer a model for improving equality of educational opportunity in El Salvador.

Policy decisions always imply trade-offs in terms of use of resources, which is why these decisions should be well informed by research. The criteria used in this paper to analyze policy options and make policy and program recommendations for improving educational opportunity are: (a) the factors that, if addressed, will make the most difference on equality according to the evidence of research-based literature; (b) the potential effectiveness of a policy for achieving equality based on evidence from research-based literature, and (c) the economic feasibility and trade-offs in the broader context of the goals of the education system.

Equality of Educational Opportunity

It is important to take an in depth look at equality of educational opportunity while thinking about barriers to equality at the level of policy. First of all, it is important to be clear about what we mean by both equality and opportunity. Secondly, while exploring policy options, if educational opportunity is seen in a general sense, rather than in a differentiated way, policy responses will also be general.

Joseph Farrell (1993) defines equity as referring to social justice and fairness. It is of a subjective moral and ethical nature, which “involves value judgments and differing understandings of what is normal or inevitable” (p.158). Equality, however, “deals with actual patterns in which something is distributed among members of a particular group” (Farrell, 1993, p. 158). For example, while there is a very unequal distribution of income in most countries, some may consider this equitable based on the belief that different jobs merit different remuneration. Somebody else, however, may assess this unequal distribution as inequitable, and argue from a more Marxist ideology that people should be paid according to their individual efforts. One the one hand, this distinction can be helpful in public policy discussion as it allows each individual to explicitly put forth her own opinion of what constitutes equity while analyzing and discussing data on equality (such as years of schooling, achievement scores, or any other quantifiable variable). On the other hand, it points to the challenge of public policy decision as it is highly contingent on ideology and personal moral and ethical beliefs, rather than on objective data. The model presented here is one based on equality of educational opportunity, meaning that it permits an objective analysis of what is acquired or achieved by different members of society based on what is available to them. It assumes that what is equitable is that all children, regardless of their socioeconomic and cultural group, should have equalopportunities to change their life circumstances.

Various researchers and educational specialists have offered models of educational opportunity. Joseph Farrell (1993) offers a four level model of educational opportunity: (a)access/input, or equal probability of entering the school system, (b) survival, or equal probability of completing a cycle of schooling including primary, secondary or higher, (c)output, or equal probability of learning achievement, and (d) outcome, or equal probability in life conditions such as income, status, and political power (Farrell, 1993). Fernando Reimers (2000) offers a five level model: (a) the opportunity to enroll in first grade, (b) the opportunity to complete first grade with enough success to go onto the next grade, (c) the opportunity to continue each educational cycle, (d) the opportunity to acquire comparable skills and knowledge to peers, and (e) the opportunity to expand social and economic life chances based on what one learns. Both models are helpful in their notion of sorting points: children, based on their economic and social conditions, are “sorted” at different stages on the educational path. Farrell’s model is helpful in offering simplifying terms such as input, output, survival and outcome to label each level or sorting point. Reimers’ model introduces an important sorting point: the completion of first grade, which, in many developing countries, sorts out thousands of children each year. The model that I offer builds upon both of these models, yet employs some distinctions in terminology and concepts. I introduce sub-levels (numbered 1-10) within each level, and indicate sorting points and obstacles by arrows. (see Figure 1) The arrow to the left represents the direct relationship between education level and higher earning potential.

The first level, attendance opportunity, is used instead of access because it is a term that is inclusive of other conditions besides geographical access[1]. For children to have the opportunity to attend school, they must not only have geographical access but also sufficient economic resources to attend and parents willing to them to school. This is the same for the level of secondary education. The arrow to the right at this first level of opportunity illustrates the loop of repetition, which often keeps children eternally restricted from going on to the next level of opportunity, often eventually due to drop out. There is a sorting point before going on to the next level that is desertion from the system, illustrated by the arrow to the left of the first level.

Figure 1. Multi-leveled model of educational opportunity

The second level of opportunity, completion opportunity, refers to the opportunity to complete basic education and then secondary education. Again, children can become caught within a cycle of repetition at this level (illustrated by the arrow to the right), leading to a high number of overage children in the education system. Eventually, however, the children who make it to this level will have the opportunity to complete a cycle. They may exit the pyramid of opportunity after completion of a cycle. The sorting point here, where many of these multiple repeaters may be, is for those who do not make it to the next level: learning opportunity. Many children will complete basic education, and some even secondary, but the skills and knowledge they acquire may be minimal due to the poor educational quality. Furthermore, children may assimilate content yet not higher order thinking skills. Therefore, this level of opportunity has two different sublevels: achievement, and skills and knowledge. One level is reflected in achievement scores measured by standardized tests, and the other concerns thinking and analyzing skills and values, more likely measured by their success in life. Success is reflected in the highest level of opportunity, life opportunity, which isalso sub-divided. Completion of higher education is linked with life opportunity. Status, income, and political power may have to do with the development of different and higher intelligences such as, social ability and analytic capacity, as well as family and social connections which can be influenced by where one goes to school. In this model, the highest level of life opportunity is social transformation. This transcends individual life opportunity, and puts as the ideal the transformation of social structures. This is relevant for an education model: if a model is based on individual achievement rather than transforming social conditions, a society will continue to be based on a system of differentiated level of opportunity. In turn, if one makes it to the highest level, while maintaining or developing the will and capacity to work towards creating a more socioeconomic inclusive society, entrenched structures based on inequality may be transformed towards more equal structures. Life opportunity, in its broadest sense, can be conceived of as the opportunity to transform one’s own life and contribute to societal transformation.

It is important to mention that this model is based on the formal education system and does not take into account the other possibilities and options for education and training for both young people and adults. For example, adult education programs and vocational training offer ways to gain access to better life options, and there are non-government organizations that offer non-traditional forms of education that operate on a different time frame, sometimes more adequate to the living situation of the participating population. While this paper is concerned primarily with policy changes in the formal education system, it is important to take into consideration these other valuable options and seek to strengthen and complement them.

The Marginalized Population of El Salvador

El Salvador is a country that has been characterized by extreme inequality, which was the primary cause of its twelve-year civil war ending in 1992. The marginalized population of El Salvador is about 40% of the population. This is the population that rarely makes it to the second level of opportunity. In 1999, 41% of the population lived in poverty, and the same percentage without drinkable water (Rivas, 2000). Rivas also describes that of this poor population, 17% lived in extreme poverty, meaning they were unable to cover their basic needs of food, clothing, and housing. This poorest 20% of the population earned 5.7% of the national income in 1999, while the wealthiest 20% of the population received 48% (Rivas, 2000). While there are marginalized sectors in the urban areas, with 10% living in extreme poverty, the rural population (42% of the total population) is where the poverty is concentrated. More than half of this population lives in poverty, and 27% in extreme poverty (DIGESTYC, 2000).

Economic options for this population are scarce. Maquilas, or sweat shops have become a large employment source, with free zones or tax free areas extending into the rural areas. Exports from maquilas have increased from 18.3% in 1991 to 43% in 1997, while traditional agricultural products have declined from 37.8% to 23% (Murcia, Paniagua, Quezada, and Rosekrans, 1999). While it is often necessary to be literate for these factory jobs, more than a basic education is not required. While analyzing educational opportunity, it is important to keep in mind this economic context: there are few incentives for the rural populations to attend school unless they have the intention of moving to an urban area for work. Furthermore, education policy should not be considered in isolation from other national policy issues. Improving equity in a country should be the prerogative of the government, incorporating all ministries, as well as of the private sector.

Educational Opportunity in El Salvador

Attendance Opportunity

This first level of opportunity, the opportunity to attend primary school, is contingent on several conditions: (a) having a school geographically near enough to where one lives, (b) being sufficiently healthy to attend, and (c) having the economic resources necessary. Although this last factor has not changed in El Salvador, there has been substantial improvement in access for both pre-primary and primary school attendance in the past decade. This is primarily due to the implementation of a World Bank financed program called EDUCO (the Community Managed Schools Program). Before 1991, 68% of urban schools and 42% of rural schools offered pre-primary school, with only 21% of the children age 4 to 6 enrolled (Ministerio de Educación, 2000c). In the past decade, and with an annual increase of 212 sections, this enrolment increased greatly. In 1999, 35% of rural children age 4 to 6 were attending school while this figure was 59% for urban children of the same age (DIGESTYC, 2000). This lower attendance for the rural population has to do with geographical access as well as other factors. This is partly reflected in the difference between enrolment figures and attendance: while 28 children are enrolled per class on average, an average of 18 may actually attend class on a given day (Ministerio de Educación, 2000c). The reasons for not attending school between the ages of 4 and 6, however, are different than the reasons for not attending primary school. Only 16% of 4-6 year olds do not attend school due to it being too expensive or because of reasons related to the home, while 65% do not go because of age (DIGESTYC, 2000). On the one hand this survey response could indicate that the child is too young to walk to the nearest school, which may constitute a geographical access problem. On the other hand, it could reflect a situation that has to do more with cultural norms than with poverty or geographical location. Only 8% in this age group report not attending due to other reasons (DIGESTYC, 2000).

The increase in primary school attendance, while not as drastic as the increase for pre-primary attendance, shows substantial improvement. In 1991, before the implementation of EDUCO, 65.36% of the rural children between the ages of 7 and 15 years attended school, where as in 1995, the figure rose to 73.5% and in 1999 to 77.6% (DIGESTYC, 1993, 1996, 2000). In 1999, 91% of urban children from the ages of 7 to 15 attended school. The national net enrolment rate reported by the Ministry of Education for 1998 was 84% for first through sixth grade and 42% for sixth through ninth grade (Ministerio de Educación, 2000a). This disparity in data is partly explained by the high number of overage children in primary school. For this population, between geographical access and economic conditions, the latter seems to outweigh the former; in other words, the opportunity cost for a family to send their child to school may be the principal factor for this problem of attendance. In looking at the reasons for not attending school, roughly one-third of rural children (age 7-15) cite the reason “muy caro” or very expensive, as a reason for not attending school. In addition, 7 out of 10 children do not attend school for other reasons, such as: the need to work, reasons related to the home, and parents not wanting them to go to school.

In terms of secondary education, the net enrolment for the urban population in 1997 was 55.2% and for the rural population 4.8% (Fernandez and Carrasco, 1998). Although according to the 1999 national survey, 34% of rural 16 to 18 year olds attend school (DIGESTYC, 2000), many of these adolescents are still in primary education. Only 9% of 19-23 year olds were attending school, either at the primary or secondary level. Roughly eight out of every ten adolescents (age 16-18) do not attend for economically related reasons. However, it is interesting to note that 17% of adolescents of this age, and 26% of adolescents age 13 to 15, do not attend school for “other reasons” (DIGESTYC, 2000). It could be the case that these other reasons have to do with not having geographical access to their grade level, as many rural schools only offer sections up to a sixth grade level. Out of all of the children who begin primary school, only 6 out of 10 finish fifth grade, indicating that there are many factors –principally economic- that cause a child to abandon school. The data reflects three major points relevant to this first level of opportunity: (a) Children tend to enroll in school at a later age in rural areas, possibly due to cultural factors and a lack of access, (b) poverty, or opportunity cost, seems to be the principal barrier to the opportunity to attending primary and secondary school, and (c) geographical access is also a likely barrier to attending secondary school and the last cycle of basic education grades six through nine.

Completion Opportunity

The opportunity to complete primary school or secondary school is still beyond the majority of the marginalized population. In the rural population, one in every three adults cannot read and write, while for the urban population this is one in every ten adults (DIGESTYC, 2000). The average level of schooling for the urban population is 6.69, while for the rural population it is less than half this: 3.18 years of school completed. (DIGESTYC, 2000). Further stratification can be identified by looking at income levels: in the rural population, the poorest 25% have completed two years of schooling while the wealthiest 25% have completed 4.3 years. This is still lower than the poorest 25% of the urban population that have completed 4.6 years (Reimers, 2000). This shows the stark disparity both between income levels, as well as the general divide in completion opportunity between the rural and urban populations.

Within the three cycles of basic education first through third grade, fourth through sixth, and sixth through ninth grade, it is often in the first cycle of basic education where children lose this opportunity to complete their basic schooling. Again, those who make it past this level are almost always the wealthiest. Only 20% of the poorest 40% of the population have completed primary school and 8% secondary, while 85% of wealthiest 10% of the population have had the opportunity to complete primary school and 69% to complete secondary (Reimers, 2000). This low completion of secondary education has serious implications for social exclusion, as “those who have not completed this level are likely to be seriously excluded from opportunities to participate in any meaningful way in labor markets or social and political organizations” (Reimers, 2000, p. 65). Furthermore, these figures are representative of the structural inequality. The likelihood that the children of the poorest families will have the opportunity to complete their schooling, especially secondary school, is much lower than it is for the wealthiest families. Studies have confirmed parental education as the strongest predictor of student achievement. This strong influence of parental education as an “indicator of the intergenerational transmission of educational inequality” is something that “has been documented in most countries for which evidence is available” (Reimers, 2000, p. 77). This points to the difficulty of breaking the cycle of poverty.

There are various factors that cause these poorest sectors to be sorted out before having the opportunity to complete their schooling. Repetition is one factor that is both a cause for lack of completion opportunity and at the same time a symptom of a deficiency in quality. Of the 58% of Salvadoran children who finish primary school, a very high proportion of these repeat a grade at least once. In 1996, 13.2% of the poorest 10% of students were repeating a grade, while this figure was 3.9 for the wealthiest 10% (Carrasco, 1999). Repetition in El Salvador has not decreased in the past decade: In 1991, the repetition rate for first grade was 17%, while in 1997 it was 18%. In second grade the repetition rate was 8% and 7% respectively (Ministerio de Educación, 2000a). For 1998, repetition for the first three grades combined was reported at 8.54% for the rural population and 6.68% for the urban. While this is the official figure, it is likely that the real figure is higher, as in Latin American countries the actual repetition rate at the primary level is often likely to be at least a third more than what governments report (Eisemon, 1997, p. 20). These figures do illustrate, however, the challenge of children getting through the first year of school.

High levels of repetition lead to high amounts of overage children in school. In 1999, there were 250,000 students that were in grade levels not corresponding to their age (CIDEP, 1999). In the year 2000, 15% of the children in first through sixth grade were overage, according to the Ministry of Education. This creates a serious instructional challenge, as children are at different developmental levels and present different needs. Furthermore, this leads to a sense of failure, and often leads to drop out (Eisemon, 1997). For the rural population, drop out rates are highest in the first three grades, being 5.88 for this level, 4.49 for fourth through sixth grade, and 3.98 for the third cycle (CIDEP, 1999).

There are many reasons for repetition, of which poverty and the low quality of education are primary reasons. Eisemon (1997) addresses these causes at three levels, all of which are applicable to El Salvador: child and family characteristics, teaching and learning characteristics in the school, and education policy. In terms of the school level, poor texts and teaching, large class size, and teacher absenteeism all present obstacles for students to effectively learn enough to be promoted. Double shifts including reduced class hours and overworked teachers, strategies such as multi-grade classrooms, and lack of adaptation of school calendars to agricultural production cycles, are policies that exacerbate these obstacles. In terms of family, the opportunity cost is very high for a poor family to send their child to school, especially if he or she is not learning. During the time of the harvest, many families opt to have their children help with production instead of attend school. Due to the high poverty level of many families, many children lack appropriate nutritional and health conditions – although this is not usually the main cause of absence. The “readiness” of the child can be a major factor for repetition, especially for disadvantaged families. Children often lack the early stimulation and prior learning necessary for their success in primary school (Eisemon, 1997; Myers, 1989; Young, 1996).

While repetition is a serious problem for the repeaters themselves, as children are caught in a loop that does not allow them to progress to the next level of opportunity or simply exit from the system altogether, it also presents a serious problem for the government. For example, the economic cost in regions such as Latin America for primary school repetition was estimated (in 1990) as being more than double the whole of multilateral assistance to the education sector (Eisemon, 1997, p. 17). Repetition is a structural problem, meaning that it is embedded in the different layers and dimensions of the society and education system, and recognizing it as such permits aiming policies towards structural solution. This type of response would be a more effective way of addressing the problem of repetition.

In sum, in thinking about completion opportunity, it is important to consider that: (a) completion of primary school for the poorest sector is as low as two in ten children and one in ten for secondary school, (b) completing secondary school is almost always a condition for social mobility in any meaningful sense, and (c) repetition is a strong barrier to completion opportunity and is a structural problem with its roots in family conditions, educational quality, and educational policy.

Learning Opportunity

To have the opportunity to learn means that even if a child comes from a disadvantaged background (of uneducated parents, extreme poverty, and a lack of early education, the child can obtain the same knowledge and skills as other children who come from more advantaged origins. At the more basic level, this can be measured in terms of achievement scores, which test for how well a child has learned the curricular content. Other learning goals are often not measured by these tests, such as “self-esteem, learning how to learn, advanced thinking skills, problem solving, and decision-making” (Farrell, 1993, p. 28). Being a good citizen, a necessary condition for working towards social transformation, is another one of these frequently unmeasured goals. Yet these characteristics are often the most important for success at the level of life opportunity. If a child completes school, but does not acquire knowledge, skills, and these characteristics, the child has not fully had the opportunity to learn. By assimilating only curricular content, the child has only had a partial opportunity. Full opportunity can be understood as assimilation of curricular content as well as the development of life knowledge and skills.

A school that provides full learning opportunity usually requires components such as good school conditions including adequate infrastructure, safety, materials, a low teacher-student ratio, school leadership and organization, an appropriate and challenging curriculum, and well-trained and supported teachers. These could be considered some of the key ingredients for an effective school.

In El Salvador, some of these conditions are partially met, while others are far from being met – especially for the most marginalized sectors. The number of teachers has not increased accordingly with the enrolment increase. The number of students for each teacher was 47 in 1997, up from 38 in 1995 (Fernandez and Carrasco, 2000). The shortage of teachers is greater in the rural areas, especially at the level of secondary school (Fernandez and Carrasco, 2000). Also, the level of preparation of the teachers is higher for the urban areas than for the rural areas: while only 12% of rural teachers have a university degree, this is true for 37% of urban teachers (Reimers, 1995). The majority of rural teachers have completed a three-year training program, yet these teachers often serve grades for which they have not prepared. Those who do get specialized training often seek employment with the private, urban sector: In a recent study to track 192 teachers trained in basic education, only 10% of these teachers were employed in rural schools, while 68.4% were employed in private schools (Barillas and Gamero, 2000).

As mentioned, achievement scores reflect a certain degree of educational opportunity and inequalities can be seen in the disparities between achievement scores between sectors. The national average in the high school standardized test (PAES) was 5.0 on a scale of 1-10 for 1999, while this was 7.5 for private schools (Ministerio de Educación, 2001). Similarly, a study by Carrasco (1999) found a significant correlation between math and language achievement scores and socioeconomic condition, where the disadvantaged students scored up to four points below other students on a scale of 1-10. A more recent study by Marin (2001) found advantages of urban students over rural students in reading comprehension and language skills. The same study showed that rural teachers were more likely to have double shifts, less likely to plan together, and reflect more of a gap between their theory and their practice – hence using outdated teaching methods. Even though as of 1995 there is a new curriculum with improved content relevancy and a constructivist focus, school practices have not changed beyond a superficial level (Fernandez and Carrasco, 2000). The most poorly trained teachers who serve the marginalized populations face the biggest challenge in implementing this new curricular focus. The teacher profile outlined in this curriculum is radically different from the profile of these teachers, who are poorly educated, poorly trained, overworked, and lack the time and support for meeting these expectations. While these teachers are the most in need of training in order to meet the new requirements, they have not received more training and support than those teachers who are already closer to the profile.

As mentioned, it is difficult to measure the development of other skills and knowledge related to life opportunity that is not assessed in standardized tests. However, some factors that contribute to their development can be identified, which are: a teaching methodology that encourages reflective and independent thinking, methodologies and laboratories that help to develop interest and scientific knowledge, the opportunity to learn a foreign language, and the ability to use a computer and internet. None of these opportunities are present in the public schools of the marginalized population (Carrasco, 1999).

The situation of disadvantage in terms of educational quality is even more critical in the light of research that reflects that quality matters the most for the lowest socioeconomic groups in terms of their opportunity to succeed in school. In less industrialized countries, the effects that schools have on student achievement are greater than the effects of socioeconomic background (Reimers, 2000). A good school can make a very substantial difference in the life of a disadvantaged child -perhaps more of a difference than it will make in the life of a child from a more privileged family.

In sum, to remove barriers to learning opportunity, it is important to consider that: (a) the poorest students are most likely to attend the least effective schools that have the most poorly prepared teachers and worst school conditions, (b) achievement scores reflect that the poorest students are doing substantially worse in school, and (c) the quality of the education that children receive is the most important variable for achievement for the most disadvantaged students; it is this that determines if they will have the opportunity to learn the knowledge and skills necessary to change their lives.

Life Opportunity

The opportunity to transform one’s social and economic life conditions means to gain access to the labor market and earn enough to support oneself. It means to have the education and social connections to engage in political and social activity. Ideally, it means to be able to go beyond satisfying one’s own needs and contribute to building a more just society. For somebody who comes from a marginalized family and community, it means breaking the cycle of living in extreme poverty and socioeconomic exclusion, and, ideally, extending this opportunity to others in one’s family and community.

Making it to higher education, which is partially subsidized in El Salvador, is a first step into breaking this cycle. Only 1.7% of the rural adult population, 20 years and above, has at least 13 years of schooling, compared to 15.9% of the urban adult population (DIGESTYC, 2000). Although this higher urban rate of university attendance is partially due to the fact that people from rural areas migrate to urban areas to attend university, it also points to that lack of education opportunity at this level in rural areas. The costs involved in migrating to the city to attend university present an obstacle for the rural poor.

In general, it is only this small percentage of the population that has the opportunity to attend university that is able to obtain sufficient income to support a family of four. As discussed in previous sections, the vast majority, especially of the rural population, abandons the education system before even completing secondary school. After twelve years of schooling the average urban income is $329.55, which is not enough to support the basic needs of a family of four. After nine years of schooling, the average urban income is $238.00, which is below the poverty line defined as $271.00 for urban zones, therefore anyone having finished three years of schooling or less lives in poverty in both rural and urban areas (DIGESTYC, 2000) . Average rural income for this education level is $114.24, which is $82.51 short of escaping rural poverty, while the urban income of $182.64 is $88.68 shy of escaping urban poverty (DIGESTYC, 2000). In sum, having the opportunity to transform one’s life means completing secondary school with enough skills and knowledge to access higher education and/or earn enough to live above the poverty line. Also, this opportunity is contingent on receiving a quality education that promotes the development of thinking skills, social skills, and values that allow for successful integration into society. And finally, a very small percentage of the population –and especially of the rural population –reaches this level of opportunity to step out of socioeconomic marginalization.

Policy Options: What is being done to expand opportunity at all levels?

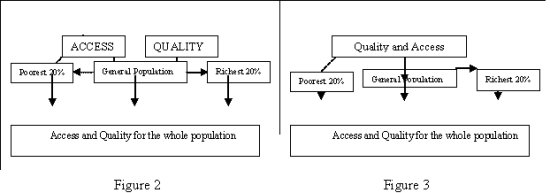

El Salvador, like other Latin American countries, has implemented policies and programs throughout the past decade to expand educational opportunity through improving access and quality. Although some of these programs are similar in strategy, countries have not taken the same routes in their approach to improving equality. This could have to do with seeing educational opportunity through a framework very different than the one presented here, for example, one that does not differentiate between levels of opportunity. It could also be the cause of the subjectivity of equity in looking at equality, as already discussed. Another possibility, linked to this subjective definition of equity, is that the governments are at different stages, or take different stances, with regards to educational opportunity. Where some may be conservative, believing that social class determines opportunity, others may be liberal in their definition and promote equal treatment, and yet others may have aprogressive definition, promoting a positive discrimination approach. This conservative position has begun to fade out along with the military dictatorships and radical conservatism that characterized Latin American countries up until the 1990’s. What seems to dominate in many countries, especially in Central America, is the liberal position. The trend in some of these countries, like in the case of El Salvador, has been to recognize the need for special attention at the level of access for the marginalized population, especially under international pressure to expand access, while assuming that generalized efforts to improve quality will also reach these populations. Figure 2 illustrates this approach, where direct actions are taken to improve access for the poorest sectors. The assumption is that the actions to improve quality aimed at the population in general will also reach the marginalized sectors, when, as already mentioned, these efforts tend to offer more benefits to the less poor population. Figure 3 represents a different approach. In this approach there is acknowledgement that the efforts to improve quality will tend not to benefit the poorest schools unless there are direct actions towards this population to improve quality. This progressive approach, which recognizes the need for special attention in quality as well as access, are often termed compensatory policies or programs. These policies, which try to compensate for the existing social inequalities, can be defined as “policies that attempt significant redistribution of education resources and opportunities by redressing existing inequalities” (Reimers, 2000, p. 32).

The programs implemented by the Salvadoran Ministry of Education in the past decade aimed at improving opportunity for the marginalized sectors have been on the level of attendance opportunity and completion opportunity, not yet reaching the next level. Furthermore, some elements of these programs, and recently adopted policies and programs, merit careful examination so that the barriers to learning opportunity do not thicken. Although these are not all of the recent programs and policies, the present discussion considers: (a) EDUCO, a Community Managed Schools Program, (b) Escuela Saludable, (d) Aulas Alternativas, (d) Educación Acelerada, and (e) general efforts to improve quality.

EDUCO is a program that started in 1991 and was initially funded by the World Bank. The goals of this program are: (a) Improving access to schools in the poorest communities, (b) improving the quality of pre-primary and primary schooling, and (c) supporting and encouraging community participation in education. The first goal, expanding access to primary school, has been met successfully, as mentioned. In terms of the second goal, however, evaluations that control for background and other disadvantage variables, conclude that the program has no impact in student achievement (Jimenez and Sawada, 1998). This could be due to the underlying assumption in the approach. This program seems to fall under the World Bank strategy of increasing the quality of education through relatively costless efficiency reforms, such as decentralization, which operate under the rationale that increased community control allows for increased relevancy, accountability and results (Carnoy, 1998, p. 47). While this accountability causes less teacher, hence student, absenteeism, this does not lead to higher achievement, which underscores the need to look for different ways to improve quality. Furthermore, research demonstrates that in low profile, or low quality, schools participation seems to consist more of ratification of proposals than debate, and these schools are the least enthusiastic about the effects of local participation and are the most unlikely to participate (Guevara, Hernandez de Rivas, Rodriguez, and Carrasco, 2000). This does not mean that the goal has been entirely unmet, rather that the schools where participation has increased may not be the poorest quality schools.

The Escuela Saludable, or Healthy School program, which started in 1995 in coordination with Ministry of Health, is aimed at detecting health problems that can interfere with learning in the poorest student populations. Also a part of this program is food provision, mental health support, efforts to involve parents in the school, training about the program, and distribution of educational materials (Fernandez and Carrrasco, 2000). The Ministry cites its achievements as a series of activities that have been carried out, such as food distribution, talks about nutrition and hygiene, workshops and trainings about health and nutrition, and distribution of educational materials, mini-libraries, and sports packages (Ministerio de Educación, 2000b). Also among the achievements of the program the Ministry cites a “decrease in absenteeism and desertion” (Fernandez and Carrasco, 1998). Civil society organizations, however, have criticized these claims by pointing out that this attention to roughly 600,000 children yearly is not enough to have a substantial impact on this population, and suggest that it is necessary to do a real assessment of the results (CIDEP, 1999). This criticism appears to be valid in the light of research on compensatory programs that demonstrates that the success of these programs is contingent on both the amount ofresources made available for them and the duration of their implementation (Driessen and Mulder, 1999). If less than fifty percent of the population is being targeted, for example, and the efforts are minimal in relation to the need, it may be difficult to meet the goals. Also, it may not be possible to see tangible results until up to ten years after implementation. Furthermore, it is necessary to control for other variables and do a longitudinal and/or comparison group study to determine if this program is having an impact. It would be more efficient to invest in a study of this type than to continue spending on this program if it’s impact is insignificant. However, the Ministry’s efforts to target resources to this population in order to contribute to their opportunity to attend and complete school are important and could be indicative of trend towards reducing inequality. Civil society organizations may help accelerate this trend if they maintain a critical stance towards the aims and results of these policies and programs.

Another effort aimed at increasing both attendance and completion opportunity is the program Aulas Alternativas, or multi-grade classrooms. The program is aimed at rural communities where there is low demand for complete sections of grade levels, and consists of combining two or more grades. The program also includes some instructional materials and training to the teachers to aide them in this type of instruction. The program started in 1996 as a pilot program for 23 communities. In 1997, it expanded to 133 communities, giving attention to roughly 4.500 students with 157 teachers serving an average of 29 students (Fernandez and Carrasco, 2000). The Ministry cites its achievements for the year 2000 as the activities of distributing teaching materials and imparting self-didactic materials and trainings to the teachers (Ministerio de Educación, 2000b). There are plans to expand this program in the coming years.

Again, it is hard to tell if this program is having an impact or not on school attendance and completion. Between 1994 and 1997, rural secondary education enrolment increased by 37% from 3.2% to 4.8% (Ministerio de Educación, 2000b). This could be due to the program, other reform efforts, other factors, or a combination of all of these elements. Distance education has also been implemented since 1994, and was serving 8,895 students in 1997 (Fernandez and Carrasco, 2000). Again, it is necessary to do a targeted study, controlling for other variables, in order to assess the effectiveness of multi-grade classrooms for attendance and completion. Yet it is also important to take into account learning opportunity. The conditions of rural teachers do not lend themselves to becoming better teachers through self-didactic strategies, especially using an instructional approach previously foreign to them. These teachers need effective support and training in order to offer the students the opportunity to learn. This is also an important consideration for students who choose to go the route of distance education. In this case, the students may altogether lack the support needed for effective learning. A comparative analysis taking into account the effect of both programs on attendance, repetition, completion, and achievement would be helpful for policy and program decisions about secondary school options.

Educación Acelerada, or the Accelerated Education program, was initiated in 2000 as a pilot project financed by the World Bank, in order to focus on and stamp out age-grade distortions (World Bank, 1998). The strategy is to work with students who are more than two years behind their appropriate grade level in order help them get to their appropriate level by going through curricular content in an intensified and condensed manner. Again, this strategy should be looked at in the light of learning opportunity, firstly, by examining the literature on similar experiences in other contexts and secondly, by assessing its impact on achievement and on other learning goals.

In terms of addressing learning opportunity, or improving quality, there are no efforts specifically directed towards the most marginalized sectors. There are initiatives for improving the quality of the education system as a whole, however, which have primarily focused on in-service training. As previously discussed, since 1995 the Ministry has implemented a new curriculum with a constructivist approach and carried out trainings, on a massive scale, to familiarize the teachers with this new approach. Perhaps in recognition of the failure of teachers to internalize constructivist teaching after several years of in-service training, the recent approach has been to continue the trend to decentralize. Initiated for the first time last year, at the end of every school year each school is given a quantity of money for training, according to the number of teachers at that school. The school is responsible for identifying their needs, training, and hiring individual consultants or organizations. These organizations and consultants must qualify to register in order for them to sell their services.

While this modality might be beneficial in terms of creating more school autonomy and improving the relevance of the trainings for the teachers, it may not benefit all the schools equally. The lowest quality, or least effective, schools are less equipped to take on this responsibility. As mentioned previously, these schools are less likely to participate and positively exploit their autonomy. Being in charge of professional development is a high level of responsibility that requires technical criteria. Also, the poorest quality schools do not have the knowledge and contacts that less marginalized schools have in order to select their trainers. Another consideration is that many of the schools that serve the marginalized populations are smaller and have fewer teachers. This implies that they will receive much less money than the large schools usually found in more urban areas. The implication of this is that the teachers that are most in need of training will have fewer resources for this than other schools. While one option is for schools to combine resources and receive trainings together, at present this is a recommendation of the Ministry, not a policy. Finally, research on in-service training points to teacher education being most effective when pre-service and in-service training are integrated and systematic, meaning that trainings are planned and carried out in a way that continually build upon knowledge and skills, instead of being dispersed and ad hoc (Villegas-Reimers, 1996; Torres, 1999).

Programs such as: EDUCO, Escuela Saludable, Aulas Alternativas, and Educación Acelerada are aimed at improving educational opportunity for the marginalized sectors. They are limited, however, to the first levels: attendance opportunity and completion opportunity. At the level of learning opportunity, at present it is unclear if these programs will have a positive effect, negative effect, or no effect on equality.

The barrier for achieving equality may not lie so much in the definition of the policies themselves, but in their implementation. The overall policies of the Ministry do refer to decreasing the remainder of the educational gap between regions and socioeconomic groups (Ministerio de Educación, 2000a). On the one hand, this policy statement reflects the acknowledgement of the existing problem of inequality in the education system. On the other hand, however, the terminology reflects an assumption that inequality is not a deep, structural problem, but that there is a remainder of inequality. Also, even though there are programs that respond to this at the level of access, it is questionable if this is a strategic policy. This type of policy, according to Haddad (1994), implies “strategic decisions (that) deal with large scale policies and broad resource allocations” (p. 4). To determine if these programs imply broad resource allocations it would be important to look at the percentage of resources directed to the marginalized populations in relation to the rest of the population, taking into account if these are national resources or external resources usually in the form of loans. Another barrier to equality seems to be the model, or conception, of equality underlying decisions at the highest level of policy. In order to chip away at the barriers to equality, it would be important to move from a liberal conception of equal treatment to all as illustrated by Figure 2 to a progressive model of discriminatory treatment as illustrated by Figure 3.

Policy and Program Options to Improve Quality

Improving equality of educational opportunity at all levels, impacting also the level of life opportunity, implies making strategic decisions towards this end. Making this type of decision means deciding to take a different path – one that will lead towards a more equitable society. In a context like El Salvador, however, with a recent history of war, extreme political opposition, and conservative dictatorships, a progressive policy decision at the strategic level may not be possible in the near future. As Haddad (1994) points out, policy changes are connected to social, economic, and political dimensions, and “any attempt to modify the system, which is perceived by one group or another as lowering the chances of their children to progress socially or economically, will meet with strong opposition” (p. 9). A decision to reorient resources to another socio-economic group would most likely be met with such resistance. However, even if this change on a strategic level is not possible at present, multi-program or program policy decisions could be made towards improving equality beyond the first two levels of opportunity. At either level, and with some possible variations in magnitude and commitment, various policy options can be explored.

One general option to consider is the implementation compensatory policies or actions, as previously explained. Some Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Colombia, and Chile, have begun taking this progressive approach in the past decade. For example, since 1991 Mexico has implemented various compensatory programs aimed at providing infrastructure and materials, training and incentives for teachers, and other actions taken to improve quality in the most marginalized sectors (PREAL, 2001). These efforts began with a program targeting only 100 schools, but expanded to 46% of public schools by 1999. According to reports, this program proved effective in improving completion rates for the targeted schools; A longitudinal assessment of the program, however, showed no significant impact of the program in learning gains (Reimers, 2002). What is important to note, however, is that the implementation deviated significantly from the design, in pedagogical approach, training, support, and the degree of components that reached the schools, and that “teacher education component was the most haphazard aspect of the program” (Reimers, 2002, p. 21). As pointed out by Driessen and Mulder (1999), for programs of this type to succeed, it is necessary to have strong policy theory, effective implementation, and consider other factors such as commitment of time and resources. Even though changing teacher practices may be very difficult, especially in the poorest quality schools, there are cases of success. In these cases, where programs were aimed at restructuring schools, students who started the program at well below the national average in reading comprehension were able to substantially increase their performance to exceed those averages. For interventions of this type to be successful, however, they should be structured around such core aspects as an emphasis on the preparation of teachers and a more demanding curriculum (Reimers, 2000, p. 33-34).

As evidenced by the discussion of the barriers to equality in El Salvador, there are various paths that could be taken to begin to chip away at these barriers. Also, as discussed, compensatory programs and policies could be a means to rid of these barriers more quickly. However, taking into consideration the magnitude and range of their causes -from late entry into the education system, lack of prior learning, repetition, desertion and lack of primary school completion, and extremely low enrolment and completion of secondary school- it is not easy to decide towards which area to direct resources. While one may want to approach the problem from various angles, this should be given very careful consideration; program and policy decisions are decisions about resources, and as Levin (1983) states in regards to cost effectiveness, “(e)very intervention uses resources that can be utilized for other valued alternatives” (p. 48). Assuming that the aim is to achieve more equality of educational opportunity at the level of learning opportunity, this is a primary criterion for deciding which route should be taken.

Secondary Education

Successful completion of secondary education is necessary for socioeconomic mobility, and, less than 5% of rural Salvadorans are enrolled at this level. Therefore, it would seem appropriate to increase investment at this level. However, it is important to consider various factors. First of all, with such a low percentage of rural children finishing primary school, it is logical that secondary school enrolment is very low. Evidently there is a demand that is not being covered, but it is dispersed instead of concentrated. In this sense, the current programs of multi-grade classrooms and distance education may be the most feasible option to improve access to secondary education for the short-term until rural primary school completion is significantly increased. An important investment at this level, as mentioned, is to carry out an evaluation of the impact of these programs on both completion and student achievement.

Early Childhood Education

In recent years, more research points to the importance of early childhood education for success in school and life. Researchers cite medical and educational research claiming that “mental growth (or) the development of intelligence, personality, and social behavior…occur most rapidly in humans during their earliest years” (Young, 1996, p. 5). As mentioned, research also points to the effects of early childhood education on improving the readiness of children to attend school, hence decreasing repetition and increasing their probability of success in school. However, this same literature recognizes that “the value of benefits that children, mothers, and communities receive relative to the cost of providing different child service inputs” (Young, 1996, p. 40) is unknown. Efforts to implement early childhood education programs in developing countries are faced with the same problems as basic and secondary education: inadequate infrastructure, poorly trained teachers, and a high ratio of children to a teacher. This may be more problematic for infants and small children, who need a safe environment and specialized attention from a primary care giver. It would take a large investment to create a childhood education program that meets these requirements, drawing resources away from an investment that could have a greater impact on educational opportunity.

Instead of neglecting this level altogether, less expensive modalities could be implemented, such as non-formal and community-based programs. These could be home-day care or parent education programs that function on a volunteer or quasi-volunteer basis. These are relatively low-cost programs that can offer early stimulation for mental and physical development (Myers, 1989, p. 29). They can also be instrumental in changing cultural beliefs, for example, about the age that it is appropriate to begin school. This could help get children into pre-primary school earlier. Such programs are being implemented in El Salvador by Salvadoran non-government and government organizations, also with assistance from international organizations, such as the World Bank and USAID (United States Agency for International Development), as well as with national resources. For the efficient use of these resources, it is advisable to learn from the successes and failures of similar programs internationally as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of these programs.

Basic Education

Many of the causes of inequality of educational opportunity can be addressed by targeting basic education. As discussed, repetition is a structural problem that constitutes a barrier to completion opportunity. It is caused by family conditions, such as poverty and lack of prior learning, as well as problems with quality and education policy. All of these problems could be addressed with a structured and targeted program aimed at improving these conditions in the least effective schools. To effectively implement a program of this type, it is important to have a model with criteria for classifying the areas and levels of need for school improvement. For this, school effectiveness research can help to provide a model of an ultimate goal, or the ultimate stage that a school should get to. School improvement literature, in turn, can help to define the process for arriving to this goal.

While there are slight variations, research points to similar factors that constitute an effective school. These factors are: professional leadership, shared vision and goals, a learning environment, concentration on teaching and learning, purposeful teaching, high expectations, positive reinforcement, monitoring progress, a learning organization, and home-school partnerships (Heneveld and Craig, 2000; Reimers, 2000, p. 29). Different schools have varying levels of development in each of these domains, pointing to the need of a clear strategy to address this variation. In this sense, it is helpful to look at schools in a framework of stages of development. Beeby’s (1966) model, while outdated and conceptually linear, lays out a model that defines four stages of development; the divisions according to levels of effectiveness offer some relevant organizing tools and insights. However, it is limited in its notion that schools can only progress from the lowest stage to the highest stage of effectiveness in a sequential and linear fashion. Also, many of the elements that constitute an effective school are not included in this model. What are helpful about the model are its criteria for classifying schools according to different characteristics. While schools do not necessarily have to progress from one level to the next, there is validity in Beeby’s warning that attempting to move to move directly from a low level of development to an advanced stage, for example, by removing teacher supports such as highly scripted materials, could cause a school to regress (p.70). Another example of this is expecting a school to govern itself completely, when it has never had this responsibility, which could cause it to fall into complete disorganization. Beeby also offers a helpful notion regarding teacher improvement: There should not be unreal expectations placed on teachers (p.73). It could be that a teacher that matches the model for the highest level of effectiveness cannot be made from the existing teacher(s) in the school. This is important to recognize in order to avoid failure in implementation. Finally, Beeby’s point that change and innovation have proven more feasible in the lowest grades (p.75-76) is a helpful insight in order to focalize efforts where impact may be the highest. The high repetition and drop out rates at this level underscore this argument.

Once a model is established of the effective school, a public school assessment can be carried out that classifies the level of need in each domain (see Appendix A). Resources could be allocated according to this level of need. In general, the lowest-scoring schools would be allocated the most resources, and highest scoring schools the least. On a more specific level, weaknesses in the different domains will demand different levels of resources. For example, one school may score very low on well being of students and not so low on teacher preparation and support while the opposite may be true for another school. The educational inputs needed to improve this school’s score in the first category may be less costly than the training needs for the other school. If resources were allocated in such a way, under a solid program design and faithful implementation, the expected result would be that schools would move towards equality in their level of effectiveness.

As mentioned, however, it cannot be expected that there will be faithful implementation, which is why it is important to draw upon school improvement research. This research sheds light on what works for changing schools, and while it is important to consider the cultural context for all proposed changes, as Reynolds (1992) points out “it is equally important that improvement programmes bring all available knowledge to the solution of continuing problems such as underachievement” (p.1282). In this case, it is particularly important to analyze the effects of compensatory programs and other efforts to improve learning conditions for the lowest socioeconomic groups.

One tool that has had relative success in several Latin American countries such as Colombia is the use of the Proyecto Educativo Institucional, or School Education Project. This is a strategic planning tool that contemplates the different domains of a school similar to the domains described for effective schools in Appendix A. This shares characteristics with the Logical Framework, which is a strategic planning tool used by international development organizations. The framework, which uses a participatory approach, includes the need to define immediate and long-term objectives, carry out a cause and effect analysis, and determine external factors that can affect the process during implementation. This tool could be effectively used in the compensatory program proposed in this paper. In this way, local Ministry officials, supervisors now termed asesores pedagogicos, or pedagogical advisors, for their newly defined role to support teachers, and the community could participate in the needs assessment, planning, and monitoring of the improvement plan for the school. Strategies such as Action Research would be particularly useful to create a learning environment and shared vision.

Conclusions

El Salvador, similar to many Latin American countries, has undergone substantial sociopolitical and economic change in the past decade, and the education system has been changing in tandem. These changes have brought a shift from a more conservative education policy approach to a more liberal approach; and combined with international pressure, have contributed to increased educational opportunity at one level, which is the level of access. A more differentiated model of educational opportunity, however, reveals that thick barriers to equality still exist – barriers that may only be chipped away at with a more progressive definition of equality. While strategic policy decisions under this approach would be the most effective in improving equality of opportunity at higher levels, this may not be possible for the context of El Salvador. Here, change towards a progressive approach will most likely be incremental. This paper has proposed a framework for increasing equality of learning opportunity by implementing a compensatory program that is aimed at improving schools incrementally and according to need.

While inequality is a structural problem that must be addressed on a national level and across governmental sectors and private and other non-governmental actors, what is considered here –educational opportunity- plays a key role in increasing the probability that the marginalized populations will transform their living conditions. Above all, this opportunity should be a gateway for this population to have a voice in public policy in order to help build a new socioeconomic model that foments their livelihood and dignity as citizens. Children born in to a marginalized population have the potential to transform their reality and contribute to a larger transformation of the conditions of their community. At each sorting point, children can go up, out, or down the scale of opportunity. The number of children who ascend to the highest level –life opportunity- will depend on what education policy decisions are made in the coming years.

References

Arrien, J.B. (1996). Calidad de la Educación en el Istmo Centroamericano. San Jose, Costa Rica: UNESCO publishing.

Barrillas, A., & Gamero, R. (2000). Estudio sobre la Colocación de Graduados del Profesorado en Educación Basica. San Salvador, El Salvador: Ministerio de Educación-GTZ.

Beeby, C.E. (1966). The Quality of Education in Developing Countries. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carnoy, Martin. (2000). Globalization and educational reform. In N. Stromquist, & K. Monkman (Eds.), Globalization Education (pp.43-61). New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Carrasco, A. (1999). Equidad de la Educación en El Salvador. San Salvador, El Salvador: FEPADE.

CIDEP , Asociación Intersectorial para el Progreso Social y Desarrollo Social. (1999). Balance Educación 99: Analisis Educativo Período 1994-1999. [Education Balance 99: Educational Analysis Years 1994-1999]. San Salvador, El Salvador: Imprenta y Encuadernación Díaz.

Dalin, P. (1998). Developing the twenty-first century school: a challenge to reformers. In A. Hargraves, A.. Lieberman, M. Fullan, & D. Hopkins (Eds.), International Handbook of Educational Change (pp.1059-1073). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

DIGESTYC , Direccion General de Estadistica y Censos. (2000). Encuesta de Hogares de Propósitos Multiples, 1999. [Multiple Purspose Household Survey, 1999]. San Salvador, El Salvador: Ministerio de Economia.

Driessen, G., & Mulder, L. (1999). The Enhancement of Educational Opportunities of Disadvantaged Children. In R. Bosker, B. Creemers, & S. Stringfield (Eds)., Enhancing Educational Excellences, Equity and Efficiency (pp.37-64).. Dordrecht. Kluwer: Academic Press.

Eisemon, T. (1997). Reducing Repetition: Issues and Strategies. Fundamentals of Educational Planning, 55. International Institute for Educational Planning. UNESCO.

Farrell, J.P. (1993). International Lessons for School Effectiveness. In J.Farrell, and J. Oliveira (Eds.), Teachers in Developing Countries: Improving Effectiveness and Managing Costs. (pp.25-37). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Fernandez, A.S.,& Carrasco, AG. (2000). La Educación y su Reforma: El Salvador 1989-1998: San Salvador, El Salvador: FEPADE.

Guevera, M.F.,Hernandez de Rivas, C., Rodriguez, & Carrasco, A.G. (2000). Los CDE: Una Estrategia de Administración Escolar, Local, Participativa .[The Educational Directives: A Strategy for School Administration, local, Participative]. San Salvador, El Salvador: FEPADE.

Haddad, W. (1994). The Dynamics of Education Policy Making. World Bank, EDI Development Policy Case Series. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Heneveld, W. & Craig, H. (2000). Schools Count: World Bank Project Designs and the Quality of Primary Education in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Technical Paper Number 303, Africa Technical Department Series. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Jimenez, E. & Sawada, Y. (1998). Do Community-Managed Schools Work? An Evaluation on El Salvador’s EDUCO Program. Development Research Group: The World Bank.

Levin, H. (1983). Cost-Effectiveness: A Primer. New Perspectives in Evaluatio: Vol 4,Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Marin, M.F. (2001). Aula Reformada: Buenas Practicas de Actualización y Buenas Practicas Docentes. Unpublished Study, REDUC.

Ministerio de Educación del Gobierno de El Salvador. (2000a). Desafíos de la Educación en el Nuevo Milenio. [Challenges of education in the new millennium]. San Salvador, El Salvador.

Ministerio de Educación del Gobierno de El Salvador. (2001). Census de Matricula Annual.(Yearly Enrolment Census).

Ministerio de Educación del Gobierno de El Salvador. (2000b). Memoria de Labores, 1999-2000. [Work Report, 1999-2000. San Salvador, El Salvador.

Ministerio de Educación del Gobierno de El Salvador. (2000c). Caracteristicas Basicas de la Educación Parvularia en El Salvador. [Basic Characteristics of Early Childhood Education in El Salvador]. San Salvador, El Salvador.

Murcia, A., Paniagua, M., Quezada, A., & Rosekrans, K. (1999). El Salvador: Transición y Participación. Social Watch 1999. Montevideo, Uruguay: Institutuo del Tercer Mundo.

Myers, R. (1989). The Twelve Who Survive. Strengthening Programs of Early childhood Development in the Third World. London: Routledge.

PREAL. (2001, March). Formas y Reformas de la Educación. [Forms and Reforms in Education]. Serie Mejores Practicas. Ano 3 / n 7.

Reimers, F. (Ed.). (1995). La Educación en El Salvador de Cara al Siglo XXI: Desafíos y Oportunidades.[Education in El Salvador in the Face of the Twentieth Century: Challenges and Opportunities]. San Salvador, El Salvador: UCA Editors.

Reimers, F., & McGinn. N. (1997). Informed Dialogue. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Reimers, F. (2000). Unequal Schools, Unequal Chances. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Reimers, F. (2002). The Social Context of Educational Evaluation in Latin America. In D. Nevo, & D. Stufflebeam (Eds.), International Handbook of Educational Evaluation(pp.1-31). Kluwer: Academic Press.

Reynolds, D. (1992). World Class School Improvement: An analysis of the implications of Recent international school effectiveness and school improvement research for improvement practice. In A.Hargraves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan,& D. Hopkins (Eds.),International Handbook of Educational Change (pp.1275-1285). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Rivas, F. (Ed.). (2000). Evaluación de la Cumbre Mundial sobre Desarrollo Social 1995-2000. [Evaluation of the World Summit on Social Development, 1995-2000]. CIDEP. San Salvador, El Salvador: Tipografía Offset Laser.

Torres, R.M. (1999). The New Role of the Teacher: What Teacher Education Model for What Education Model? In R.M. Torres, Aprender para el Futuro: Nuevo Marco de la Tarea Docente. Madrid, Spain: Santillana Foundation.

Villegas-Reimers, E., & Reimers, F. (1996). Where are the 60 million teachers? The Missing Voice in Educational Reforms Around the World. Prospects, Vol. XXVI. No 3.

UNESCO. (2000). World Education Report. The Right to Education. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

World Bank. (1998). Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Adaptable Program Loan in the Amount of US$ 88.0 Million to the Republic of El Salvador for an Education Reform Project. Report No. 17415 – ES.

Young, M. (1996). Early Childhood Development: Investing in the Future. Washington DC: The World Bank.

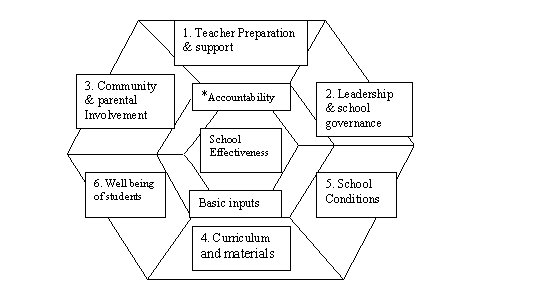

Appendix A

Domains of School Effectiveness: A means for improving schools according to need.

Each domain may be at a different level of development in each school. Also, each domain implies differences in spending in terms of amount and time (ongoing, periodic, one-time investment). The following domains would have to be assessed based on criteria for determining how much and what type of investment is necessary for improvement in that domain.

1. Teacher Preparation and Support: Pre-service and in-service training conceived as one teacher education system. This is ongoing need that tends to be costly.

2. Leadership and School Governance: Leadership and the ability of the school to govern itself requires training and ongoing support. This also tends to be relatively costly.

3. Community and Parental Involvement: The active involvement of parents, children, and other community members in the school, including both resource management and administration as well as curricular aspects of the school (what and how the children learn). This implies knowledge of team-work, consensus building, and some technical criteria, for which training may be necessary. This training may not need to be as intensive and ongoing as the training for domains 1 and 2, hence could be less costly.

4. Curriculum and Materials: A high quality and demanding curriculum, as well as materials relevant to the population, are essential for effective learning. The cost of this varies, depending on magnitude and frequency of their adaptation.

5. School Conditions: Necessary conditions for an effective school include basic infrastructure, safety and hygiene, and a teacher-student ratio that allows for effective teaching. This costs involved in this domain may be on a one-time or periodic basis, and not recurrent like domains 1-3.

6. Well-being of Students means adequate nutrition, health, clothing, and other basic needs met in order to allow them to attend school. This may require instituting a school-feeding program, providing uniforms, and/or financial aid for poor students/families for attending school.

*Accountability is built into the first three domains: Effective teacher preparation, leadership and school governance, and parental and community involvement, allow for ongoing assessment of progress and means of dividing responsibility between the stakeholders.

Footnotes

[1] Both Reimers and Farrell discuss these conditions as well, not limiting the ‘access’ solely to geographical access.